A lack of vitamins and minerals from food increases NHS hospital admissions

In a nutshell

NHS hospitalisations highlight alarming lack of vital vitamins and minerals

Evidence that such malnutrition caused by lifestyle choices unrelated to economics

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are associated with poor mental health

I recently ran across an article in the Guardian Newspaper with the attention-grabbing headline “Hospital admissions for lack of vitamins soaring in England, NHS figures show”. The author’s opening sentence reads:

“The number of people admitted to hospital in England because of a lack of vitamins or minerals is soaring, according to analysis of NHS figures”

I found the article difficult to understand so decided to summarize and describe their data, and describe what I think may be the cause. I’ll review the following:

Evidence of low vitamins and minerals

Possible reasons for lack of vitamins and minerals

Implications of less nutrient-dense diet

Solutions

Before continuing, I want to point out that I made a decent effort to track down the NHS data underpinning the newspaper article. I searched the publications of the Lord Darci’s report to Parliament (see below), I searched for links to Prof. Kamila Hawthorne mentioned in the article, I searched for output from the PA News Agency which appears to be the source of the analysis, and I contacted the author of the article. Everything I tried failed so I’m relying on the limited data provided by the Guardian newspaper.

Evidence of low vitamins and minerals

The Guardian presents two types of data, namely Hospital Admissions because of Lack of Vitamins or Minerals, and Hospital Admissions for Any Reason but also with Vitamin or Mineral Deficiency.

The first thing I note is something the data cannot help us understand at all. That is, without knowing how many total hospitalisations there were in the time periods, we can’t say whether or not these data represent a significant risk compared to other reasons for hospitilisation.

However, we can say that there are some pretty interesting trends playing out.

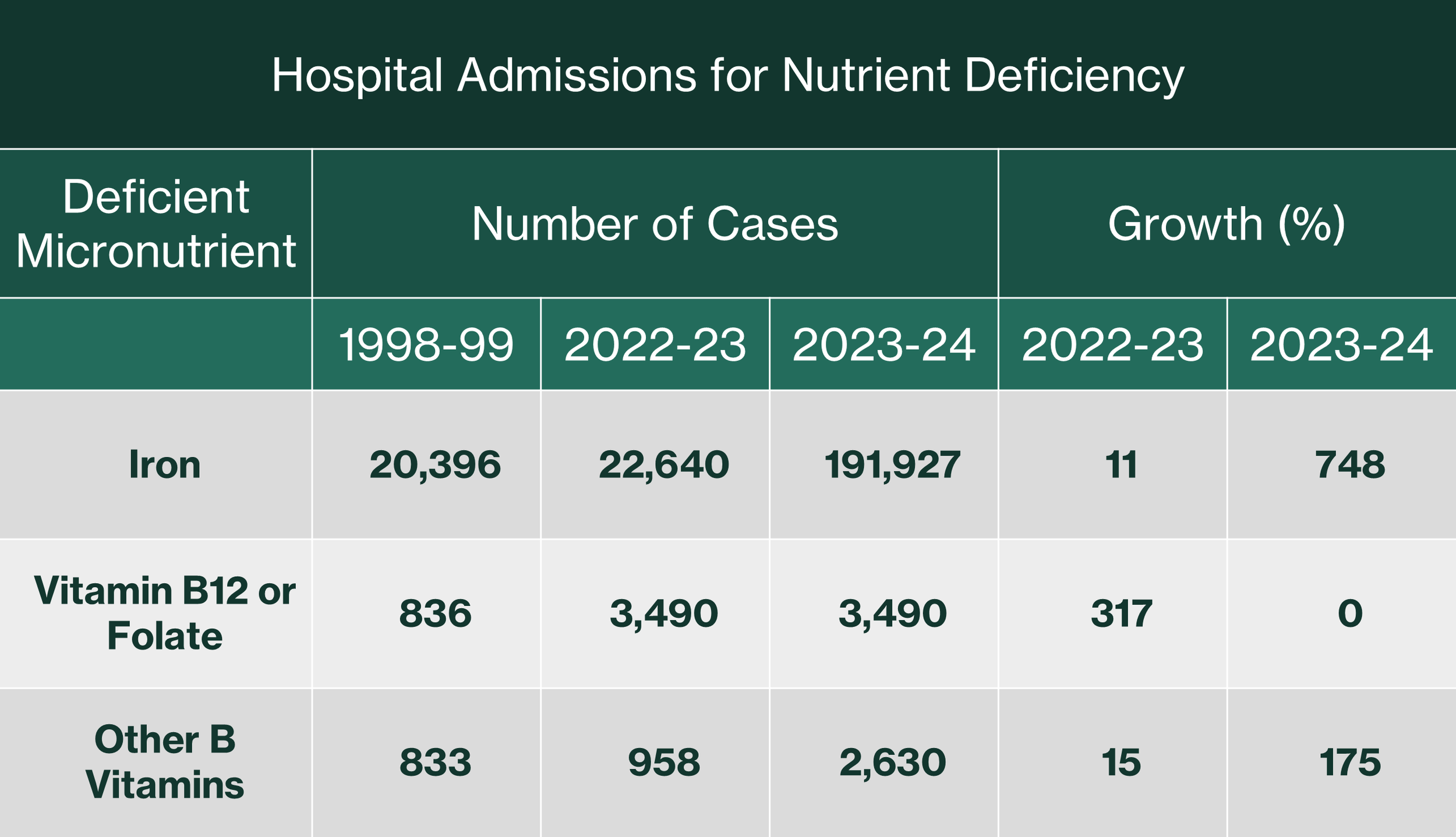

Hospital Admissions because of Lack of Vitamins or Minerals

I’ve summarised data for hospital admissions for which lack of vitamins or minerals is the primary reason in Table 1. There are a few points to note here. Firstly, the data are for deficiencies in iron, vitamin B12 or folate, and other B vitamins only. Secondly, the data is from three time periods, namely 1998-99, 2022-23, and 2023-24. I’ve highlighted the growth between those periods (comparing 1998-99 with 2022-23 and comparing 2022-23 with 2023-24).

From the longer term data (comparing 1998-99 to 2022-23) deficiency of vitamin B12 or folate is a concern but not so much for iron and other B vitamins. Consider the following:

Increases in hospitalisation due to deficiencies in iron and other B vitamins were 11% and 15%, respectively. If you consider the length of time between the two data sets, these amount to less than 1% growth annually. This is a simple analysis that may not represent what happened in the intervening period, but it’s the best I can do

Increases in hospitalisation due to deficiency in vitamin B12 is, conversely, quite large at 317%, or roughly 14% annually averaged over the period

The short-term increases (2022-23 to 2023-24) are eye-opening. Consider:

Hospitalisation due to deficiencies in iron have increased 748% in just one year

Hospitalisation due to deficiencies in other B vitamins have increased 175%

Table 1: Long- (1998-99 to 2022-23) and short-term (2022-23 to 2023-24) data showing hospitalisations caused by vitamin and mineral deficiencies

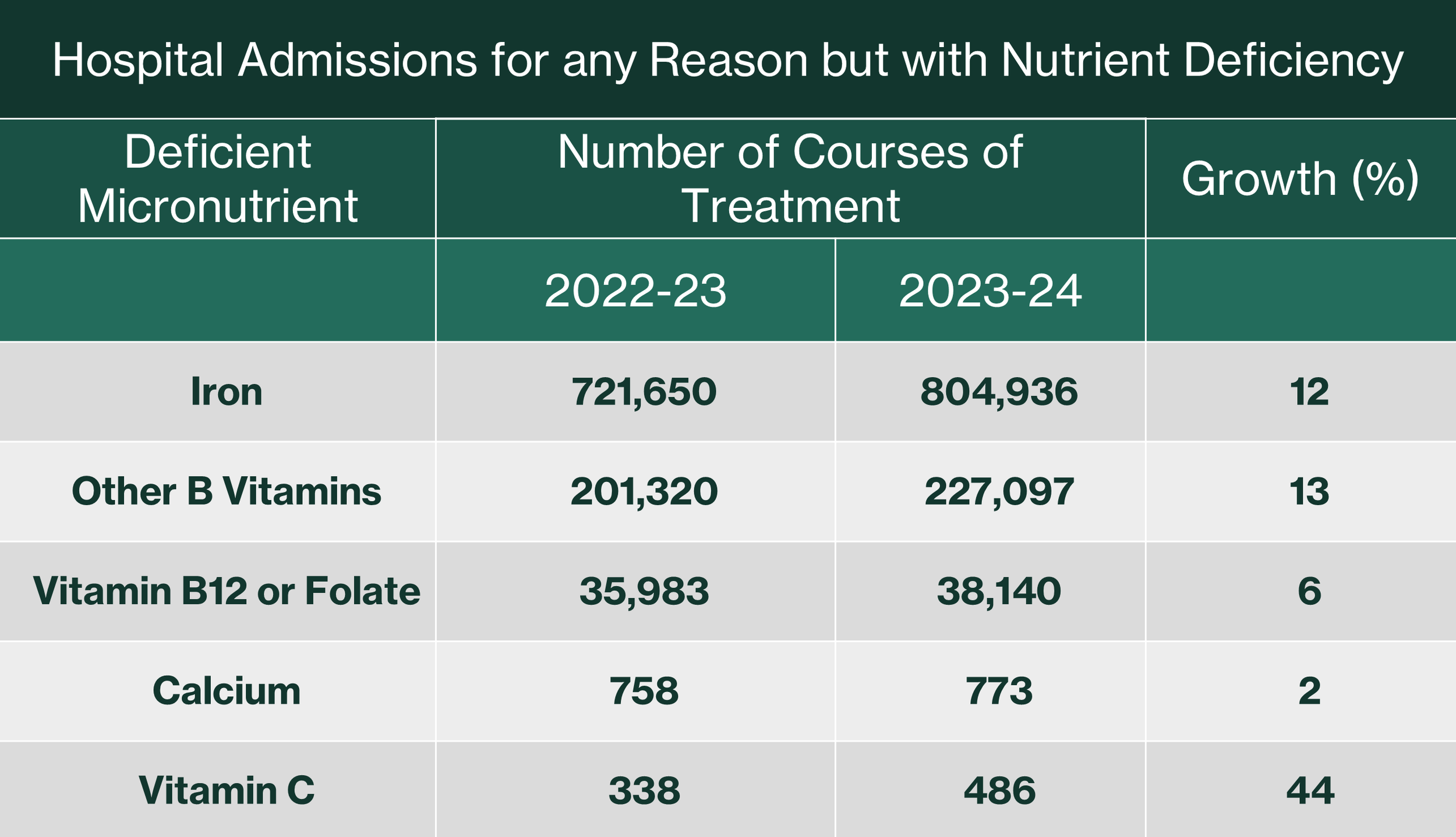

Hospital Admissions for Any Reason but also with Vitamin or Mineral Deficiency

Data for hospitalization for any reason that but also presenting with nutrient deficiency are summarized in Table 2.

The first thing to note here is that Table 1 presents cases whereas Table 2 presents courses of treatment. I have no way to know how comparable those two metrics are. For the purpose of this exercise, however, I’m going to assume that each course of treatment in Table 2 is given to a single case and is, therefore, comparable to a case.

Table 2: Short-term data for any type of hospitalisation also presenting with vitamin or mineral deficiency

The short-term data in Table 2 (no long-term data provided) highlight deficiencies in Calcium and Vitamin C as well as the three presented in Table 1. In addition to the additional deficiencies, the number of 2023-24 cases in Table 2 is much larger than those noted in Table 1. Consider:

Iron - 804,936 vs 191,927 is a 4-fold increase

Vitamin B12 or folate – 38,140 vs 3,490 is a 11-fold increase

Other B Vitamins – 227,097 vs 2,630 is an 86-fold increase

Possible reasons for lack of vitamins and minerals

I’ll present and discuss what the Guardian highlights as potential reasons and I’ll offer an additional root cause.

Reasons presented by the Guardian

The Guardian quotes Professor Kamila Hawthorne, Chair of the Royal College of Physicians (RCGP) as follows:

“The near ten-fold rise in admissions for patients with a diagnosis of iron deficiency and a fourfold increase in folate deficiencies – caused primarily by a lack of nutrition in the diet – is particularly troubling”

The article goes on to highlight how recent price increases may have contributed to the problem:

“We have seen fresh, healthier foods spike in price over the last few years, making a nutritious diet increasingly unaffordable for some, while fast foods are cheap, are filling and easy to access but are low in nutritious content”

The article infers that an overall increase in poverty may be driving sensitivity to price increases:

“A recent survey of RCGP members found that 74% had seen an increase in the number of presentations linked to poverty in the last year…”

Let’s see what we can make of these. On the issue of poverty, I found data in the Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England: Technical Annex, Figure 1.9. The incidence of different types of poverty in different demographics between 2001 and 2021 are presented and show at best declines and at worst no change as follows:

Children in poverty of any category – decline from 31% in 2001 to 29% in 2021

All people in poverty of any category – decline from 23% in 2001 to 22% in 2021

All people in deep poverty – no change from 15% in 2001 to 2021

In addition, the graph shows a fairly stable trend (no great peaks or troughs) despite coming out of the dotcom recession in 2001, the 2008-2010 recession caused by the banking crash and bailouts, the 2016-2017 Brexit fallout, or the 2020-2021 Covid lockdown economic shocks. Can we rule out a very recent spike in rates of poverty? No. However, given the resilience of that metric to past economic shocks, plus the fact that we don’t know the size (e.g., barely perceptible vs orders of magnitude greater) of the increase in presentations linked to poverty reported by the 74% of GPs, I am skeptical.

Let’s think consider also the notion that “fast foods” may be preferred in times of need. I do accept that such things are accessible and cheap on a per unit basis. However, I reject completely that they are filling. We know that the opposite is true because their high carbohydrate content affects our hormones in such a way that we are compelled to consume more. Conversely, eating nutrient dense proteins and fats reduces food craving, snacking, and in my experience, is ultimately cheaper.

All that said, I am completely on-board with the belief that what we are witnessing in the NHS is driven by a lack of nutrition in our diet.

My alternative root cause

I think a lack of nutrition in the UK diet is most likely driven by a reduction in the quality of what we choose or are able to consume, largely unrelated to affordability and poverty. This decline in food quality is driven by three underlying factors:

A long-term switch from real food to industrially processed ingredients

A long-term decline in the nutrient density of fruit, vegetables, dairy and meats

A recent switch from natural fats and protein in dairy and meats in healthy omnivorous diets towards vegetarian and vegan preferences

Long-term switch from real food to industrially processed (fast) food

The consumption of industrially processed food (referred to as ultra-processed) has increased over the years [1]:

“…over recent decades, the availability and variety of ultra-processed products sold has substantially and rapidly increased in countries across diverse economic development levels, but especially in many highly populated low and middle income nations.”

The average UK daily energy intake from ultra-processed food (UPF), minimally processed food (MPF), and processed food (PF) is covered in reference 2 as follows:

“On average in the UK, UPF contributes to over 50% of daily energy intake, with nearly one third of energy intake provided by MPF, and only around 10% by PF…”

Long-term decline in the nutrient density of fruit, vegetables, dairy and meat

The concentration of a range of micronutrients (including iron) in fruit, vegetables, dairy and meats has been decreasing since the 1940s. This has been caused by changes in agricultural practices whether related to reduced plant and animal diversity, plant and animal varieties primarily bred for yield at the expense of nutrient-density, greater capital intensity, or destruction of the soil microbiome resulting from each of those.

Recent switch from fats and protein in dairy and meats in healthy omnivorous diets

Before addressing the recent decline in consumption of dairy- and meat-based diets, let’s remind ourselves why this actually matters.

Animal-based food is more nutritious (density and bioavailability) than the most nutritious plants. This applies to both marine and land-based animals. Plants are not a good source of two of the vitamins and minerals named in the Guardian article. Iron from plant-based diets is not easily absorbed by humans, in contrast to the ready bioavailability from animal-based diets. B12 is present only in trace amounts of some fruit and vegetables other than algae or unless they have undergone fermentation. Animal based diets, conversely contain B12. Each of these points is discussed here.

If my simple web-based search is to be believed, the UK population, especially younger people, does appear to be moving towards a meat-free diet. Consider the following:

“Currently, 12% of the UK population follows a meat-free diet, which is approximately 6.4 million people. It seems that going meat-free is still a popular trend, however, as a further 14.6% of the population, around 7.8 million adults, is hoping to be meat-free in 2025.”

Sadly, younger Brits appear especially keen to reduce the nutrient-density of their food:

“A meat-free diet is most likely to appeal to the younger generations. Overall, half of generation Z (50%) and over a third of millennials (36%) are planning to be meat-free in 2025.”

Implications of less nutrient-dense diets

Nutrient deficiencies of the type mentioned in the Guardian article have been linked to a number of so-called chronic diseases. The types that concern me most, especially in light of the move away from meat based diets amongst young people, are those associated with mental health problems. A recent survey of children’s mental health in England revealed the following:

“A 2023 survey of children and young people’s mental health found that 20% of children aged 8 to 16 had a probable mental disorder in 2023, up from 12% in 2017. Among those aged 17 to 19, 10% had a probable mental disorder in 2017, rising to 23% in 2023.”

Early life, and especially adolescence, can be fraught with difficulty. The last thing we should wish is for our children to suffer from avoidable mental health difficulties.

The perceived risks associated with food lacking adequate levels of vitamins and minerals prompted the British Medical Journal (BMJ) to react. In 2024, the BMJ published an editorial in which they compare the risk of consuming industrially processed ingredients to that of smoking cigarettes:

“It is now time for United Nations agencies, with member states, to develop and implement a framework convention on ultra-processed foods analogous to the framework on tobacco.”

Before leaving this topic, I’d like to make a point that is important for me. I advocate for a n=1 approach to nutrition, meaning each of us has to figure out and decide for ourselves what is good for us. I disagree with anyone who declares that a particular diet type has universal application be that carnivore, omnivore, vegetarian, vegan, or any of their variants. I do advocate for everyone to proceed on the principle that the human holobiont (body and associated microbiome) has evolved to benefit from nutrient-dense, bioavailable food. All that said, I hope that someone choosing a vegan diet is aware of the fact that strict adherence will necessitate supplementation of important B vitamins and iron.

Solutions

Consuming healthy, real, nutrient dense food strikes me as the best way to achieve optimal nutrition and avoid the health problems associated with malnutrition. My go-to spot for advice on nutrition and recipes for preparing real food is the Weston A. Price Foundation in America. Amongst other things, they emphasize the importance of fat-soluble vitamins found in natural fats, organ meats and seafood. They also have a comprehensive, searchable site full of understandable advice.

For example, you’ll find information-packed articles on iron and vitamin B12.

Summary

The Guardian newspaper article draws attention to an obvious long-term lack of vitamins B12 and folate in the English population and a dramatic short-term increase in deficiencies of iron and other B vitamins (Table 1). Unfortunately, this may be the tip of a poor nutrition iceberg in England. Less obvious signs of vitamin and mineral deficiencies are apparently orders of magnitude higher (Table 2) for vitamins B12 or folate (11-fold) and other B vitamins (86-fold).

In my opinion, such nutrient deficiencies may often result from poor dietary choices unrelated to economics. I fear that many of us do not fully appreciate the health implications of our individual choices. This is especially unfortunate in the case of our children. There is well-documented evidence showing an increase in mental health issues at the same time as younger people are choosing to eat less dairy and meats.

I don’t yet see clear evidence for causation but I’ve seen enough evidence for a strong relationship between a healthy diet and robust mental health to make me very wary.

Data Sources Investigated for Background Information

As mentioned above.

Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England

Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England: Technical Annex

References

Lane MM, Gamage E, Du S, Ashtree DN, McGuinness AJ, Gauci S, Baker P, Lawrence M, Rebholz CM, Srour B, Touvier M, Jacka FN, O'Neil A, Segasby T, Marx W. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ. 2024 Feb 28;384:e077310. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-077310. PMID: 38418082; PMCID: PMC10899807.

Dicken SJ, Batterham RL, Brown A. Micronutrients or processing? An analysis of food and drink items from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey based on micronutrient content, the Nova classification and front of package traffic light labelling. Br J Nutr. 2025 Jan 13:1-43. doi: 10.1017/S0007114524003374. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39801244.