Dietary Fibre

In a nutshell

Dietary fibre is not necessary for all of us and may be harmful to some

The human gut microbiome flexibly responds to plant- and animal-based diets

Gut lining nutrition can be supplied by a range of metabolites

Few nutritional recommendations are as universally accepted as the need for dietary fibre. I consume fibre in my diet because I feel better when I do and I’ve assumed that’s because it feeds my gut lining.

I’ve always harboured niggling doubts about dietary fibre’s universal benefit, however. I could never really understand why, for example:

Groups such as the Inuit seem to thrive without much, if any, fibre

Modern carnivores avoid fibre in favor of a carnivore diet

Our ancestors’ height declined when plant-based food was consumed more regularly

So many of my vegetarian friends have IBS and try to reduce dietary fibre?

The recent clinical trial showing that fermented foods did a better job than a high fibre diet of increasing gut microbiota diversity (commonly considered to be healthy) and improving human immune function caused me to re-evaluate my long-held belief about dietary fibre. I dived into the literature and this is what I’d like to cover:

What is fibre, what are its effects, and why so much confusion?

Human evolution and metabolic flexibility

Sources of gut lining nutrition

What is fibre and what are its effects?

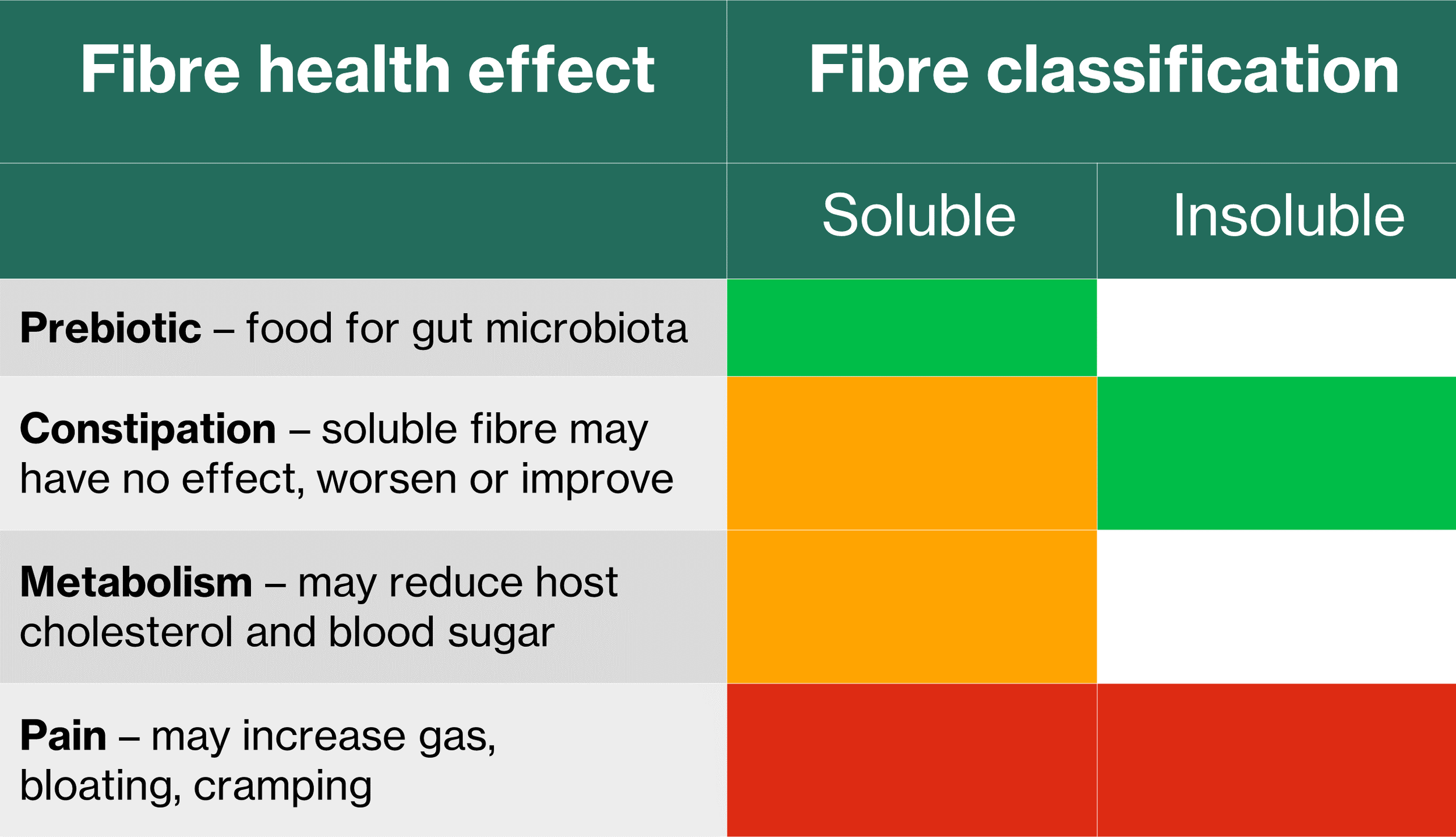

Fibre comes from plant-based foods and is the part of the plant that is not used directly by the human body. We can divide fibre into soluble and insoluble (Table 1). Many vegetables contain soluble fibre but things like psyllium husk, flax seeds and oatmeal contain high amounts.

Table 1: Classification of fibre as soluble or insoluble and their effects as prebiotics and on constipation, metabolism, and pain. Green = mostly positive effects; amber = mixed effects; red = potentially harmful; clear = no effect

Benefits

Soluble fibre dissolves in water and is what I’ve previously described as microbiome accessible carbohydrates (MAC). It acts as a prebiotic to be fermented by our gut microbiota resulting in beneficial metabolites called short chain fatty acids (SCFA). A SCFA called butyrate is considered to be a particularly important nutrient for the human gut lining [1].

Insoluble fibre stays solid in the human gut and is believed to improve gut movement and may alleviate constipation. It is not fermented and is eliminated as fecal matter.

A mixed bag

Soluble fibre has also been shown to have mixed effects on constipation and human metabolism.

Harms

Unfortunately, fibre is also associated with poor health. Soluble and insoluble fibre in some people may contribute to the painful symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and the more serious Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Eliminating fiber, in fact, has been shown to help some people with a type of IBD [2]:

“…the administration of a fiber-free diet prevents the development of colitis and inhibits intestinal inflammation…”

This seems ironic when considering that one of the benefits of fibre is supposed to be the production of butyrate to feed our gut lining.

Why the confusion?

Why is something that is apparently as important as dietary fibre associated with such mixed results, including harm? I suspect it has something to do with how different people are from each other plus our still very rudimentary understanding of the gut microbiome [1]. Consider the following:

We are mostly different from each other. The similarity in gut microbiota between any two people ranges from 0% to, at best, 30%

Definitions remain ambiguous and contested, and no one still really knows how to describe a “healthy” gut microbiome. For example, high microbial diversity, normally assumed to be a sign of good health, has been associated with diseased states

Investigations of the human gut microbiome are still quite limited:

Preclinical (mouse) nutrition studies often use unnatural and calorifically ambiguous diets in studies of macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbohydrates)

Human studies rely mostly on fecal samples which are not demonstrably representative of the whole human gut. They may be somewhat more representative of the central part (lumen) of the lower intestine, for example. The extent to which the mucus layers and upper intestine are represented by fecal samples is still poorly understood

Human studies have focused on bacteria with little still known about the role of fungi and archaea in the microbiota and viruses in the wider microbiome

The vast universe of gut microbial metabolites is poorly understood. We know a little about the role of SCFA and bile acids but have practically no insight to the complex and metabolically active glycans

If, as appears likely, our knowledge of the gut microbiome is still so limited, where else might we turn for insight to the importance of dietary fibre to gut health? I’ve been impressed by recent insight into human evolution, contemporary hunter-gatherers, and metabolic flexibility, so let’s consider those also.

Human evolution and metabolic flexibility

Evolution of the human diet

Humans have lived a hunter-gatherer life for 99.6% of the past 2.5MM years of our existence. In that time we have always eaten a range of plant- and animal based foods but their relative proportions have varied over time [3] (Figure 1) and place [4]. Our animal-based diet peaked around 2MM years ago when we were considered apex carnivores getting more than 70% of our diet from large animals. Over time whilst the the size of our prey declined most of our ancestors continued to hunt and consume largely a meat-based diet. Around 10 thousand years ago, we began to domesticate plants and animals for what we now consider agriculture [3].

Figure 1": 2.5 million years of human dietary evolution

It is important also to consider the likely variability that our ancestors faced [5]:

“Consumption of animal foods by our ancestors was likely volatile, depending on season and…foraging success, with readily available plant foods offering a fallback source of calories and nutrients.”

Modern hunter-gatherers

A recent study of 229 contemporary hunter-gatherer societies provides interesting insight to the enduring preponderance of dietarey variation and high animal-based proportions [4]:

No single diet represents all hunter-gatherer societies

73% of the groups studied derived most of their energy from animal-based foods compared to just 14% getting most of their energy from plant-based foods

20% of the groups studied were considered to be entirely or largely dependent on animal based foods. No groups were as heavily dependent on plant-based foods

Three important conclusions for me:

Humans are adapted for a mixed diet of plant- and animal-based food

Animal-based nutrition has always represented the larger proportion for people eating naturally

Our ancestors adapted to variability in their preferred food [3,4]

That final point suggests an evolved dietary flexibility. Being able to switch between different types of food was likely important for the survival of the human species.

Metabolic flexibility

It is known that when healthy, the human body is capable of amazing metabolic flexibility. This means that a healthy body can switch between fat, carbohydrates and protein for energy depending upon availability. Considering that we evolved alongside and are inseparable from our microbiota, it seems reasonable to assume that our gut microbiota also evolved dietary flexibility [5]. Indeed, it has been shown that [5]:

“…the human gut microbiome can rapidly switch between herbivorous and carnivorous functional profiles…”

We are adapted for a variable diet of plant- and animal-based food. How then did the human gut lining stay healthy when fibre was not always a principle dietary component but was often “a fall-back source of calories and nutrients”? This is where things get interesting.

Sources of gut lining nutrition

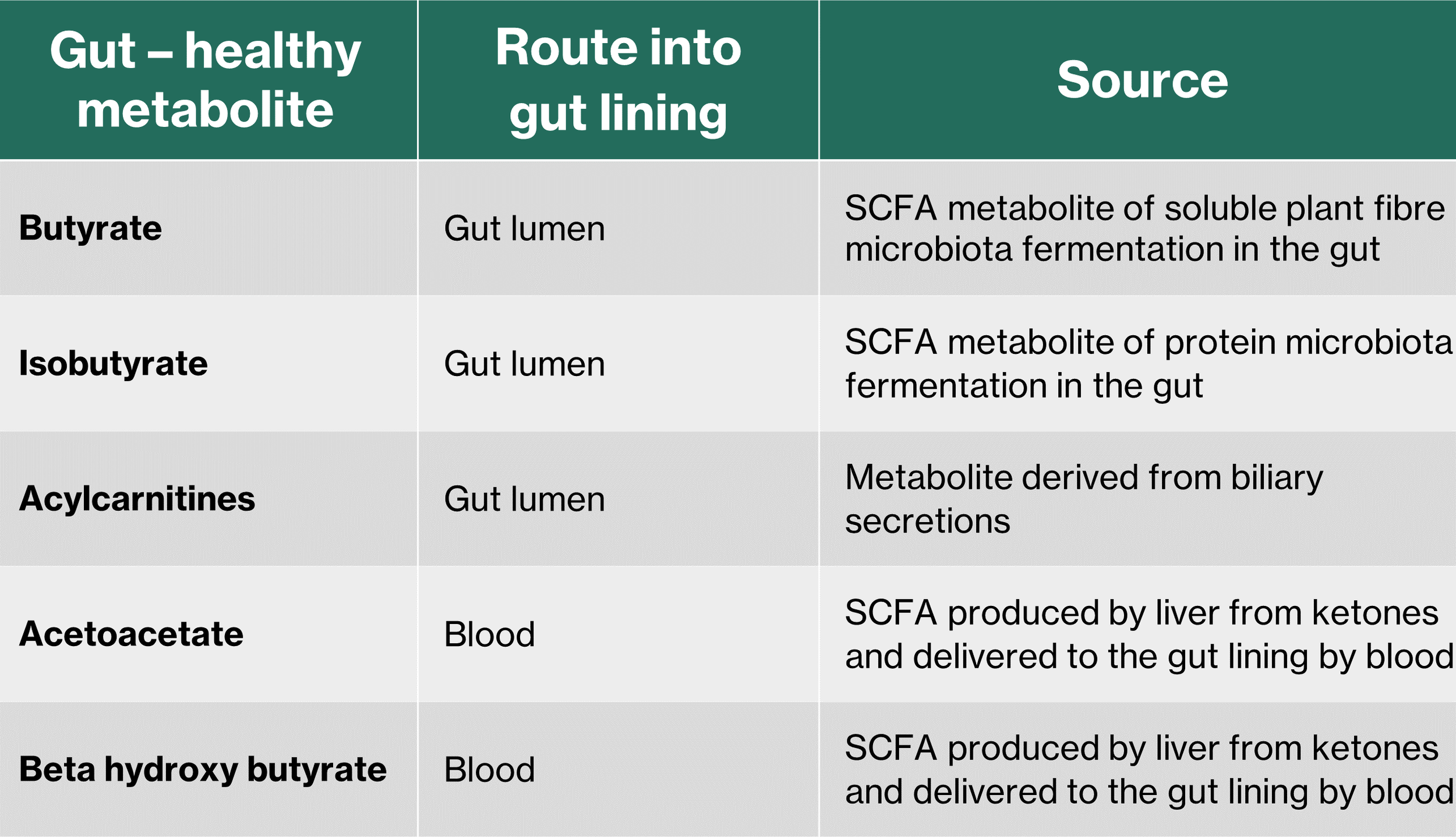

In the past I assumed that I needed fibre in my diet so that it could be fermented by my gut microbiota to produce butyrate and that butyrate fed my gut lining. However, it transpires that butyrate is just one of five molecules (discovered so far) that can feed our gut lining (Table 2) [1].

Table 2: Different metabolic metabolites which nourish the gut lining (Reference 1)

Instead of just one, there appear to be four SCFAs that we know of so far which feed our gut lining. In addition to butyrate produced by microbiota fermentation of plant fibre, isobutyrate is a SCFA produced in the gut, only this time protein is fermented instead of fibre. Two other SCFAs to benefit the lining of our gut are acetoacetate and beta hydroxy butyrate which are produced by our liver and transported to the gut lining by our blood.

The fifth element of gut nutrition is a compound called acylcarnitine which we derive from bile acids in our intestine.

A plant-based diet, IBS, and IBD

I’ve often wondered if my friends who suffer from the awful pain produced by IBS and IBD favour a plant-based diet because they want fibre for their gut health. Sadly, it seems that their choice of diet may be the cause of their distress. It has been demonstrated, in an animal model of Crohn’s disease (a type of IBD), that a fibre-free diet can inhibit the disease [2]. Furthermore, it has also been shown that a fibre-free real food diet may be used for long-term treatment of Crohn’s [6].

Are my friends in the unenviable position of having characteristics that are strongly adapted to consume our ancestral animal-heavy diet of meat and fat [3]? Our modern human genetics, body type, and metabolism still mostly resembles those of our carnivorous ancestors [3]. We have only relatively recently moved away from our ancient diet but those changes are:

“…not significant or long enough to change substantial carnivorous biological features that prevail until today”

I hope that anyone suffering from things like IBS and IBD realise that we can maintain a healthy gut lining without plant fibre. Perhaps more animal-based ingredients is worth considering, even for a short time to see if it helps.

Summary

Our ancestors adapted to eat a mixture of plant- and animal-based food. The relative proportions of plant- and animal-based ingredients for which each of us is adapted may be highly variable. Against this backdrop, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that dietary fibre appears to help some people and may be harmful to others.

I’m left wondering if the misguided notion that dietary fibre is a universal need is actually a symptom of too much reliance on processed foods. Could it be that processed carbohydrate-heavy consumption destroys metabolic flexibility and prevents us from producing a full complement of beneficial metabolites to feed our gut lining? In that scenario, our only recourse may be to eat plant fibre with its inherent risks.

The good news is that for those of us who are metabolically flexible, there are many ways to feed our gut lining, with or without consuming plant fibre.

References

Sholl J, Mailing LJ, Wood TR. Reframing Nutritional Microbiota Studies To Reflect an Inherent Metabolic Flexibility of the Human Gut: a Narrative Review Focusing on High-Fat Diets. mBio. 2021 Apr 13;12(2):e00579-21. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00579-21. PMID: 33849977; PMCID: PMC8092254.

Fiber-deficient diet inhibits colitis through the regulation of the niche and metabolism of a gut pathobiont

Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Yearbook Phys Anthropol. 2021; 175(Suppl. 72): 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24247

Cordain et al (2000) Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets

David, L., Maurice, C., Carmody, R. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature1282

Svolos V, Hansen R, Nichols B, Quince C, Ijaz UZ, Papadopoulou RT, Edwards CA, Watson D, Alghamdi A, Brejnrod A, Ansalone C, Duncan H, Gervais L, Tayler R, Salmond J, Bolognini D, Klopfleisch R, Gaya DR, Milling S, Russell RK, Gerasimidis K. Treatment of Active Crohn's Disease With an Ordinary Food-based Diet That Replicates Exclusive Enteral Nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2019 Apr;156(5):1354-1367.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.002. Epub 2018 Dec 11. PMID: 30550821